Building Your Own Bible Index

I'm finding much value in an in-progress, manually curated, linked list of biblical references

Over the last few months, I’ve been using the Zettelkasten method to take better notes. To my delight, one of the most valuable uses has been creating a manually-curated Bible index.

A Zettel… What?

If you already know what a Zettelkasten is, you can confidently skip this section.

A Zettelkasten is a collection of linked notes. Each note represents a single, atomic idea, and you manually define links between notes as you identify patterns and relationships – almost like creating your own private Wikipedia. This process creates knowledge, similar to how our brain creates synapses between neurons as it makes sense of the world around us. The resulting note archive supposedly helps you to better organize and retain content you consume, identify and capture your own ideas – your knowledge – and be more productive as a writer or content creator.

The seminal Zettelkasten was a collection of 90,000 index cards manually curated by noted sociologist Niklas Luhmann. He had a numbering system, similar to the Dewey system used by librarians, to insert every single card into a universal hierarchy. He also had index notes that registered the “coordinates” of closely related cards. Luhmann claimed that “having conversations” with his Zettelkasten enabled his prolific output, having authored over 70 books and 400 scholarly articles over a 30-year career.

Modern technology has made the idea much more tractable. Popular tools in the space include Obsidian, Roam Research, Zettlr, and several plug-ins for the Visual Studio Code editor. These tools deliver meaningful improvements over the index card approach, such as full text search, tags, automatic backlinks (“which notes link to this one?"), orphan detection (“here are unlinked notes”), and note graph visualizations.

A Zettelkasten contains several types of notes. Fleeting notes are brief ideas captured in-flight, to be fleshed out later. They’re like breadcrumbs or reminders of ideas (or reactions to ideas) that you encounter as you read, watch, talk, listen, or think. At the end of every day (ideally), you process your fleeting notes. You extract literature notes – references to others' ideas, in your own words, with citations you can reference. You create permanent notes, which build on literature notes to capture your own thoughts and ideas, and how they relate to each other and to others' ideas. Fleeting notes, as the name suggests, are typically discarded once processed.

As the archive grows, you likely will need index notes – literally lists of links to other notes on the same topic or aspect. This mimics part of the structure Luhmann used. In modern Zettelkastens, there’s less of a need to insert every note into a single numbered hierarchy, thanks to the digital features I enumerated above. Nonetheless, some people still prefer universal numbering.

My Bible Index

I started my Zettelkasten in May, and have slowly grown it to about 150 notes as I write this article. To my own surprise, a “note-in-progress” that has been particularly useful is my Bible index.

Here’s the concept. I created a note to list every book, chapter, and section (the headings) in the NIV translation. I haven’t completed the outline yet – I add new chapters and sections as I evolve the index.

Off the bat, the index is useful because I can search for a name or concept, and see which Bible sections reference it. This isn’t particularly powerful – I know that a study environment like Lumina or Logos does a better job searching biblical concepts. But the note is handy when I remember the general location of a verse or passage, but can’t remember the exact chapter or verse.

However, the index really shines as a place to “hang” links to other notes that elaborate on specific passages or sections. This has numerous uses. Essentially, whenever I find anything interesting that references a Bible passage, I create literature or permanent notes around it, and I link to them from the relevant section of the Bible index. This could look like an insight or meditation from a sermon or Bible study, or an interesting translation note, or an illustration I think of. My Zettelkasten isn’t limited to Bible-related content, but for that kind of notes I’m finding that the index is a powerful helper.

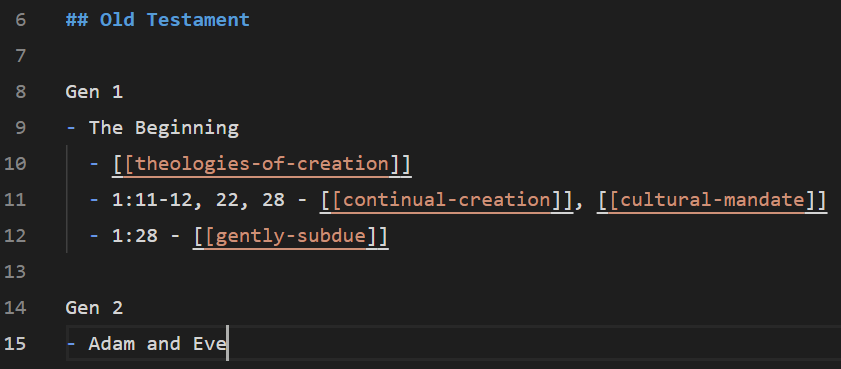

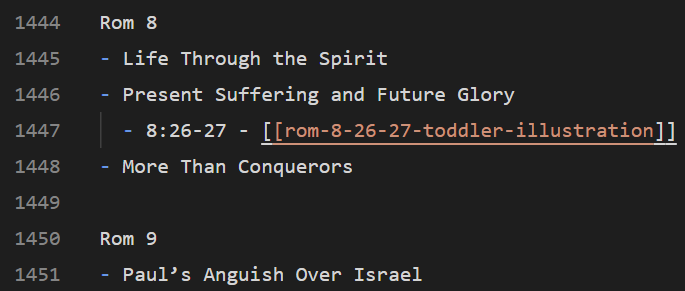

Here are some images illustrating what it all looks like (I use the free Foam VS Code plug-in):

The “[[gently-subdue]]” text links to its namesake note. It’s just like a web link – I click it, and the note opens in a new tab. I took this note from an article explaining that the Hebrew word translated as “subdue” in Genesis 1:28, kabash, conveys gentle subduing – not of a violent or destructive nature. That note references the original article, in case I ever want to read it again, or credit it in my own work.

The note linked here is an illustration of Romans 8:26-27 that came to mind as I read these verses in my devotional time some days ago. Linking to the note from the corresponding passage entry guarantees that I’ll consider the illustration if I’m preparing a study or sermon on this passage.

What excites me is that over time, I expect each section to link to multiple notes, capturing all that I have processed about it: reflections, applications, illustrations, theological doctrines, debates, etc. In fact, in the image above you can see that this is already happening in Genesis 1’s “The Beginning” section.

If you’re using the Zettelkasten method for biblical studies, I’d be interested in learning what tips and techniques are working well for you. If you don’t use the method, I would encourage you to prayerfully consider it. I know that adapting any new “high-ceremony” method can feel intimidating, but I can assure you it’s time well spent. The first link in this article has exhaustive resources. For simpler “quick start” guides, I recommend these two articles. (You don’t have to use the same tools as the authors.) If you prefer a book, the go-to reference is Sönke Ahrens' How To Take Smart Notes.

Tags: #bible , #zettelkasten